Originally published on genealogyatheart.blogspot.com 19 Apr 2015

The term “brick wall” in genealogy means an impasse has been reached and further knowledge is unavailable. Conferences are always filled to capacity when the topic of how to break through a wall is presented. Those blocks affect us physically, through wasted time and resources, and emotionally, as frustration and disappointment. It’s no surprise we’re interested to find a way through that obstacle.

Remember, though, that there are two sides to every wall. The frustration of needing to detour from my intended route may cloud my view of a solution. What I can’t clearly see ahead is probably safe and sound, just not yet accessible. Isn’t that the reason why walls were built in the first place – for protection? Next time you encounter a brick wall ancestor have a Zen moment and know the missing information is most likely safe somewhere just waiting to be found.

When a family member invited me to be her travel partner on an upcoming business trip to Salt Lake City I was delighted. The Family History Library has always been on my bucket list but with work and other commitments, a vacation there wasn’t visible on my horizon. With the hotel and plane reserved, I forged ahead with research goal setting and planning, my fourth rule of genealogy.

“Failing to plan is planning to fail.” –Alan Lakein

My goal was to find clues on how to climb over at least one my top 10 walls in the four days I would be visiting.

To accomplish my goal, I identified who I would be researching. This was difficult as I have a large family tree which results in many walls. I decided to select 5 from my family and 5 from my husband’s side. I cheated a bit and included spouses so my actual 10 was more like 15.

Then, I followed my number 1 rule of genealogy – write down everything you know and what you want to know – for each of the selected individuals. I also added where I found the information to prove what I did know. Why? Through experience I’ve learned that family lore is just that – a word of mouth tradition that someone may have misheard, misunderstood or mythologized. Think the childhood game, telephone, where a sentence is whispered child to child with the last player repeating aloud what he/she heard. The last oral sentence is not the same as the first oral sentence. Just like the game, there is some similarities in family lore from the time of the original telling but not necessarily the whole story.

In the late 1990’s I discovered the truth about family lore the hard way. Happily clicking away on an online tree I had discovered and saving the info to my own tree, I never stopped to look where the poster had found his sources. I spent several days adding many individuals to my husband’s side only to learn late one evening that, according to the online tree, he was the great grandson many times removed of Odin and Frigg, the Norse god and goddess. My spouse is an awesome husband, a devoted dad, a dedicated employee and a loyal friend but it’s a stretch to believe his Grandpa was the founder of the runic alphabet and his Grandma was a sorceress. He, understandably, liked what I found. I had to spend many hours deleting the line one individual at a time and have since checked sources before including new information in my tree.

“Genealogy without sources is mythology.” -Unknown

Definitely a painful but valuable learning experience!

I have also found it useful to review my previously discovered sources before researching further on a line I haven’t looked at for a while. There may be a hint in plain sight that I missed earlier or by reviewing the record, I may gain a new perspective.

So in preparation for my trip, I pondered my sources for my husband’s 4th great grandfather, Wilson Williams, born in 1754 in Roslyn Harbor, Nassau, New York. He is found in the 1790, 1800, 1810, 1820 and 1830 Federal censuses as living in North Hempstead, Queens, New York and he has been documented in several texts for his service during the American Revolution, as a witness in two court cases, and for being appointed to maintain the highways as he operated a stagecoach and a ferry to bring visitors between Long Island and Manhattan. An accomplished carpenter, two of his homes still stand and have been on the Roslyn Landmark Society’s home tours several times. What I could not discover was when he died and where he was buried. Collaborating with four cousins I met online, a hired genealogist, two research trips to Long Island and Troy, New York where his son had moved in the 1820’s, calls to numerous churches where he may have been a parishioner, cemeteries where he might have been buried, library and historical society visits and hours spent searching online over 16 years uncovered nothing.

I placed Wilson as my 10th brick wall as I was fairly certain that the five of us had checked every possibility in determining his death and burial.

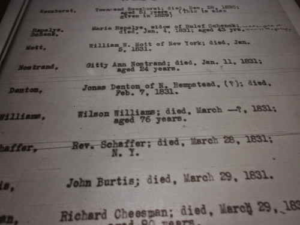

At the Family History Library, I shared my information on Wilson with a genealogist and asked for her suggestions on where to go next. She recommended checking microfilms of birth, marriage and death records for any church denomination of which Wilson may have been a member. I narrowed the search to Presbyterian, Quaker and Dutch Reformed as Wilson’s grandchildren were members of those churches and his wife, Margaret, was buried in the Dutch Reformed Church Cemetery. Many of the microfilms did not have indexes and the process was exhausting. After several hours I got a text from my family member who asked if I was ready to go to dinner. “On the last microfilm, be done soon,” I responded. “Meet you there,” she replied. Minutes later she appeared on the scene and asked if she could help. “I’m looking for a record for Wilson Williams. I’ve been through this film already but found the index at the very end. I’m just double checking that I didn’t miss him.” “I’ll do that,” she volunteered as I collected the other films to refile. In less than 30 seconds she asked, “Is this who you’re looking for?” I glanced at the screen.

Stunned, I couldn’t respond. I reread the words. Tears of joy moistened my eyes. If I had not found the index and double checked, the wall would have remained. Ironically, the family member who found the record is a DAR because of Wilson.

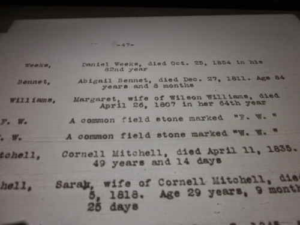

The next day I found another microfilm source for the cemetery where Wilson’s wife is buried:

So the “W.W” on the “common field stone” buried in the same plot as wife, Margaret Hicks Williams, was Wilson Williams and he had been where he should have been the whole time. The answer was clearly right there but none of us had found it. How had Wilson remained invisible for so long?

“Leave no stone unturned.” -Euripides

Most likely, the field stone with just initials was either missing entirely or not noted by the Find-a-Grave volunteers transcribing and photographing the cemetery because they would have no idea what W.W. stood for.

When I returned home and was adding the pictures and citation to my tree I noticed that the cemetery was in Success, New York. Success? I thought the cemetery was in Nassau. The microfilm noted that North Hempstead became Success which became Manhasset. Sometime after the book was published it became Nassau.

So why weren’t the records at the church? The church secretary I had contacted told me the church does not have records of the burials. Doing a google book search I found that Onderdonk’s (1884) History of the Dutch Reformed Church mentions that the early records were sketchy. To complicate the situation, a minister had died and the congregation was not in agreement on hiring a replacement. Half wanted to have a new pastor sent from the Netherlands while the other half wanted to hire a pastor from New York. Consequently, the church ended up with 2 pastors. After ten years, one pastor took half the congregation and started another church a few miles away. He took the records with him.

The records I was viewing were a transcription from the 1940’s copied by a Josephine Frost. She noted that her transcript was from a book by Onderdonk that was in disrepair. Frost was unable to find the original church records that had been donated to the Long Island Historical Society but they were available when Onderdonk published his book. There are only 12 copies of Frost’s book. They are in Cincinnati, OH, Indianapolis, IN, Harrisburg, PA, Ann Arbor, MI, 2 in Chicago, IL, Ithaca, NY, Independence, MO, Edmond, OK, Albany, NY, Provo, UT, and La Jolla, CA. The Family History Library in Salt Lake City has a microfilm of one of these books.

Wilson Williams spent his entire life in Long Island, New York yet the 13 records of his death do not reside where he lived and died. Sometimes looking in the most logical place will not give you the answer. I had to detour more than 1900 miles to get over the wall.

The microfilm record gave me far more information on Wilson then just his date of death. Next time, I’ll tell you more about the meaning of Wilson’s fieldstone marker.