Originally published on genealogyatheart.blogspot.com on 10 May 2015.

A extra special welcome to my readers from across the pond – Australia, Finland, Great Britain, Ireland, Netherlands, Slovakia, Taiwan, Turkey, Ukraine and closer to home – Canada and of course, the good ole U.S.A. Happy Mother’s Day to All!

My day will be spent being spoiled by my family, recuperating from my recent conference in New York City, processing what I learned, and planning how I can incorporate it in my work – both in counseling and genealogically. The conference, Learning & the Brain, Educating World-Class Minds: Using Cognitive Science to Create 21st Century Schools, was phenomenal So many passionate educators, psychologists, and physicians from around the world united to discuss research findings on how to prepare students for being global citizens. I kept thinking about my family tree. I call my husband and me Mutts – as in belonging to no special breed. Our people have migrated across several continents for lots of reasons and I bet your family tree is very similar to ours.

Every time I visit the Big Apple I am reminded of a family paradox. My husband’s family was early Dutch settlers who operated a farm on the East River in what is now the Wall Street district. A large bank currently sits on the farm property and that particular bank owns the mortgage on our home. I don’t think that’s right. It’s downright absurd. My husband agrees that his family has never done well with real estate ventures and selling that farm on what is currently such expensive property validates our opinion.

While walking around Manhattan this past week my thoughts turned to Ghislain1 and Adrienne Cuvellier de la Vigne, Walloons who emigrated from Leiden to New Netherlands with their children in 1624.2

Born about 1586 in Valenciennes, France, Adrienne’s maiden name most likely refers to her father’s occupation, which in English would be a cooper. Coopers made barrels and utensils, primarily out of wood. Ghislain’s last name could also give us a hint as to his family’s profession, Vigne means vineyard in French. I’d rather like to think of this as a match made in heaven instead of a marriage to consolidate business – the vineyard owner’s son and the barrel maker’s daughter but I will never know. I do know the family stayed intact and together through much adversity to create a new life in a new world.

Although a truce between Holland, France and Spain began in 1609, about the time of Adrienne & Ghislain’s marriage, there was no telling if it would be continued after its 1621 expiration. Complications further arose in the region between the Roman Catholic and Protestants. Valciennes was part of the Netherlands but ruled by Catholic Spain. Adrienne& Ghislain were Protestant. We know from Baptism records of their children that by 1618, the family had relocated to Leiden, Holland, an area that was known to be safe and tolerant.3 There the family adapted by changing their names; Adrienne became Ariantje and Ghislain became Willem Vienje. (I’ll continue to use their birth names.)

How the family was selected by the Dutch West India Company to settle in New Netherlands is not known. Hart (1959) mentions that a wealthy merchant and founder of a Lutheran congregation in Amsterdam, Herman Pelgrom, was living in Nuremberg where he married a Susanna Cuvelier in 1578. Pelgrom’s four sons from his first marriage were involved with the New Netherland’s Company in Amsterdam by 1609.4 Some researchers believe Susanna Cuvelier Pelgrom was related to Adrienne and tipped her off about the opportunity but I can find no connection. Perhaps the Vignes’ heard town gossip and volunteered to go. However they were selected, the family must have been eager to start a new life as land was scare in Holland and the promise of religious freedom must have been enticing.

In the Spring of 1624, two ships, the Eendracht (Unity) and the Nieuw Nederland (New Netherland), sailed into the North (Hudson) River, bringing the first colonists to New Netherlands. “Although we do not have a Netherlands record regarding the departure of Ghislain and Adrienne (Cuvellier) Vigne and their children Marie, Christine, and Rachel, they certainly were on one of these vessels, as their son Jan would be the first male child born in the new colony, or at least the first male child who survived and remained there (Sara Rapalje was the first female child born in New Netherland).”5

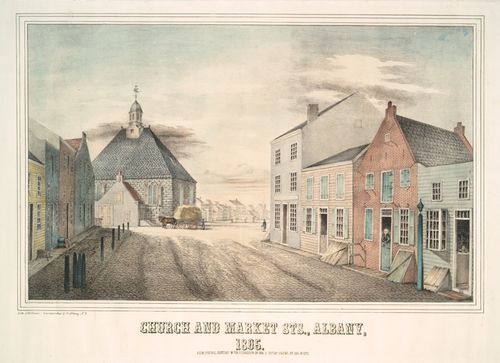

Have you ever sailed on New York’s Harbor? Each time, I marvel at the breathtaking view of the Manhattan skyline and reflect on the past hopes and dreams of immigrants as they approached Ellis Island and the promise of what Lady Liberty stands for. That is not what greeted the Vignes’. Instead, they were met by a French ship blockading the Dutch for the purpose of claiming the land for the French king. “The Dutch vessel, ‘rendered imposing by two cannons’ forced the French to leave rather than fight. The way clear, Captain May brought some of the immigrants 144 miles up the Hudson River and docked at Fort Nassau” (what is now Albany, New York).6

The following year, the Vignes’ began farming in Manhattan. The family grew with the addition of son, Jan. Happiness was brief; by 1632 Ghislain had died leaving Adrienne with 2 minor children as the eldest daughters, Marie and Christine (from whom my husband is descended), had married. Marie married Jan Roos and shortly after his death, Abraham Ver Planck. Christine married Dirck Volgersen.

Eleventh Great Grandma Adrienne did not remain a widow for long. Jan Jansen “Old Jan” Damen, emigrated to New Netherlands about 1634. Old Jan was a warden of the Dutch Reformed Church and owned a large piece of land just west of the Vigne farm. Combined together, the land tract ranged from Pine Street north to Maiden Lane and from the East River to the Hudson River. We’re talking prime Manhattan real estate today! Before the marriage, a prenuptial agreement was signed. In part, it reads “Dirck Volgersen Noorman and Ariaentje Cevelyn, his wife’s mother, came before us in order to enter into an agreement with her children whom she has borne by her lawful husband Willem Vienje, settling on Maria Vienje and Christina Vienje, both married persons, on each the sum of two hundred guilders … and on Resel Vienje and Jan Vienje, both minor children, also as their portion of their father’s estate, on each the sum of three hundred guilders; with this provision that she and her future lawful husband, Jan Jansen Damen, shall be bound to bring up the above named two children until they attain their majority, and be bound to clothe and rear the aforesaid children, to keep them at school and to give them a good trade, as parents ought to do. This agreement was dated the last of April 1632.”7

The prenuptial did not insure tranquility in the family. On June 21, 1638, Damen sued to have Abraham Ver Planck and Dirck Volckertszen “quit his house and leave him the master thereof.”8 Dirck countered with a charge of assault and had witnesses testify that Jan tried to “throw his step-daughter Christine, Dirck’s wife, out of doors.”9 Records show that Adrienne remained married to Old Jan but continued a positive relationship with her adult children. This must have placed her in a difficult position.

Old Jan’s character is further shown in 1641 when, as a member of the 12 Man Council he was one of only three on the committee who wanted to exterminate local Native American tribes.10 Although out voted, Damen persisted. In February 1643 he “entertained the governor (Kieft) with conversation and wine and reminded him that the Indians had not compiled with his demands to make reparations for recent attacks. ‘God having now delivered the enemy evidently into our hands, we beseech you to permit us to attack them,’ they wrote in Dutch on a document that survives today.”11 The Governor agreed thus Kieft’s War, a three year conflict between the Algonquin tribes and the Dutch resulted. It was the begining of the end for Damen. His neighbors horrified by the bloodshed nicknamed him “the church warden with blood on his hands” and expelled him from the local governing board.”12 I wonder how Adrienne felt. Was she ostracized by the townsfolk along with her husband?

Leaving politics, Old Jan began to amass considerable wealth in a new way – as one of the owners of La Garce, a privateering venture run between 1643-1646.13 (If you don’t know French, you really must do a google translate of La Garce. This is what makes genealogy so wickedly interesting!) You also read correctly that Old Jan financed a privateering venture, aka piracy. When you think of La Garce, think Pirates of the Caribbean. Records show that in April 1645 the vessel returned to New Netherlands with goods of tobacco, wine, sugar, and ebony seized from two Spanish ships in the West Indies. In 1646, it returned from the area off the Bay of Campeche, Mexico with a load of sugar and tobacco.14

In 1649 Old Jan returned to Holland due to a court case in which he was defending Peter Stuyvesant, the last Dutch Director General of New Netherlands, leaving Adrienne behind on the farm. He died before returning to her, in 1651.

I wonder how the neighbors treated Adrienne after Old Jan was gone – did they shun or embrace her? There are no records to tell us. I speculate that Great Grandma lived quietly until her death in 1655.

And what happened to the farm? Damen’s “heirs sold his property to two men: Oloff Stevensen Van Cortlandt, a brewer and one-time soldier in the Dutch West India militia, and Dirck Dey, a farmer and cattle brander. Their names were ultimately assigned to the streets at the trade center site. Damen’s was lost to history.”15

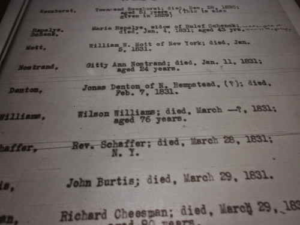

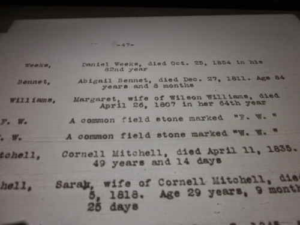

Unfortunately, so was the whereabouts of Adrienne’s burial. Christina Vigne’s husband, Dirck, and her sister, Maria Ver Planck, were sued by Dutch Reformed Church Elder Claes Van Elstandt on March 8, 1658, for nonpayment of Adrienne’s grave. The pair claimed to have given money to Rachel Vigne’s husband, Cornelius Van Tienhoven, who had absconded with it 16 months prior. The court ordered all heirs to pay for the grave.16 The debt was paid but there is no mention in the records of where the grave was located.

On this Mother’s Day, I wanted to remember Adrienne. Although she died 360 years ago there are mother’s today still seeking safety from brutal spouses, war, and religious conflict. My Mother’s Day wish is that they can persevere and be as strong as Adrienne.

1Ancestry.com. New York, Genealogical Records, 1675-1920 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2004.

2Dorothy Koenig and Pim Nieuwenhuis, “The Pedigree of Cornelia Roos, an Ancestor of Franklin D. Roosevelt,” New Netherland Connections [NNC] 2(1997):85-93, 3(1998):1:1-5, correction 3:2:34-35 corrected Ghislain’s originally recorded name as Guillaume.

3Parry, William. New Netherland Connections Quarterly, Vol 3 No. 1, Jan-Feb-Mar 1998.

4 Hart, Simon. The Prehistory of the New Netherland Company: Amsterdam Notarial Records of the First Dutch Voyages to the Hudson. Amsterdam: City of Amsterdam Press, 1959. 22.

5 Macy, Harry Jr. The NYG&B Newsletter, Winter 1999, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Society at http://www.newyorkfamilyhistory.org (search for the pdf – you don’t have to be a member to view this)

6 McNeese, Tim. New Amsterdam. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 2007.56.

7 New York Historical Manuscripts: Dutch, Volume 1, ed. and trans. by Arnold J. F. Van Laer. Baltimore, 1974

8 McVicar, Hugh D. McVicar Post Ancestry: The Ancestry of George Wesley McVicar (1884-1936) and Naomi Theresa Post (1881-1951) : 16 Generations of Family from Toronto to Scotland, New England, New York & Overseas. Madison, Wisconsin: E. J. Burch, 2003. 38.

9 Ibid

10 “Blackmail as a Heritage: Or New York’s Legacy from an Earlier Time.” In The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, 771. New York: Century, 1887.

11Lupton, Eric. “Ground Zero: Before the Fall.” In The New York Times, June 27, 2004.

12Ibid.

13Jameson, J. Franklin. Privateering and Piracy in the Colonial Period:. New York: A.M. Kelley, 1970. 9.

14New York State Secretary’s Office. Dutch Manuscripts, 1630-1634. Vol. II. New York: Weed Parsons, 1865. 36.

15Lupton, Eric. “Ground Zero: Before the Fall.” In The New York Times, June 27, 2004.

16 Rollins, Sarah Finch Maiden. The Maiden Family of Virginia and Allied Families, 1623-1991: Aker, Alburtis, Butt, Carter, Fadely, Fulkerson, Grubb, Hagy, King, Landis, Lee, Scudder, Stewart, Underwood, Williamson, and Others. Wolfe City, Tex.: Henington Pub. ;, 1991. 20.