This is the fourth blog I’ve written about my Baines family research. Thousands of online family trees have the wrong pedigree. Today I’m focusing on the errors regarding Mathew’s purported father, William Baines, based on the research that I discovered that provided a pedigree in court records and due to a church porch that was once bought and sold.

I am not convinced that William Baines of Stangerthwaite is the father of Mathew Baines of Wyersdale. I mentioned previously that I don’t hold much credibility when someone is known to be of a particular place as people do relocate. Perhaps they are considered from a certain location as they lived there for the longest period in their life or sometimes, it is thought of the place they were born. It also could be where they died and was buried. So, it is possible to have a father associated with one location and a son with another. That’s not my concern.

The distance between the two locations is about 25 miles. Stangerthwaite is located in the parish of Kirkby Lonsdale, now Cumbria but at the time Mathew and William resided there it was Lancastershire. Wyresdale remains located in Lancastershire. The distance is also possible. It was discovered that a William Baines did have a bastard child so it is feasible he left Stangerthwaite and moved to Wyresdale for a time and started a new life there but he was more likely the father of the William purported to be Mathew’s father and not Mathew’s father.

As with Mathew, no baptismal record for William was found. He has been mis-pedigreed to have a father named Adam due to someone who found a birth record for a William but the poster neglected to understand that “d. an infant” meant that the child had died as an infant. That Adam did not have another child he named William. Thousands of trees copied the wrong information and therefore, the wrong pedigree.

William has been recorded as marrying Deborah Hatton but no marriage record was provided. Online trees show Deborah Hatton, daughter of Thomas Eaton and Isabella Lathom Hatton to have died about 1650, with no sources. She could not have been the Deborah who married William Baines of interest as that Deborah was living in 1660. It is understandable how Deborah Hatton was identified as William Baines’s wife as her father Thomas was purportedly buried in Goosnargh, Wyersdale, again, with no source.

There has been one document found showing William Baines, Dorothy Baines, and Mathew Baines all in the same location at the same time – an arrest of the men for attending a Quaker meeting in 1660 in Lancaster. Dorothy was often a nickname for Deborah. Unfortunately, no relationship was provided.

Mathew remained a Quaker as he later married in that faith to Margaret Hatton and had his five children baptized as Quakers. He died while emigrating to Bucks County, Pennsylvania in 1686/7, likely on a William Penn ship.

No other records were found for Dorothy or Deborah Baines so she likely died shortly after the 1660 arrests of her probable husband and son.

But this leads us to another problem with the trees. William was said to have remarried a Sarah Hepworth but no marriage record was found. The couple have been recorded to have three children, James, born 1655, Joseph, 1657, and John/Jonathan, 1658, though Johnathan was likely confused with a son of James.

James, based on court document copies found in a local church, was a devout Quaker like his father William. The court record provided that James had a brother Joseph and they resided next to each other. James had purchased the land from his father, William in May 1685. William had purchased some of the property from his own father, William Sr., in 1651. The eldest William retained partial land as noted by another document that showed 2/3 of his estate was under sequestration in 1653. That portion was likely sold out of the family to John Robinson and Robert Hebblethwaite but was repurchased by grandson James in 1662 and 1677.

We also know that William [Jr.] had a brother named Joseph who was a Quaker. This was also confirmed by another source that noted both men were imprisoned for not paying tithes in 1664 in Sedbergh, Yorkshire.

Many records for William have been found: In 1661 he refused to take an oath, in 1662 he was imprisoned in Yorkshire Castle, he was again imprisoned in Yorkshire Castle in 1664, he paid a hearth tax in Pooley Bridge, Westmorland, near Sedburgh in 1669-1672, he received a fine in 1670 for attending a Quaker meeting, he was brought to court in Richmond for not paying his Easter tithe in 1674, he was imprisoned in Lancaster Castle for nonpayment of tithes in 1675, and returned to Richmond Court in 1675-1676 as a defendant in a case brought by a local minister.

He may or may not be the William who renounced being a Quaker in Lancaster in 1679.

No further records were found for William and he may be the William who was buried on 18 September 1687 in Lancashire, England.

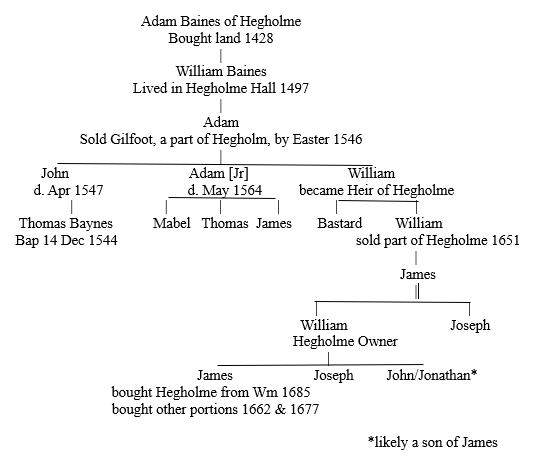

From one additional document regarding an interesting panel in a local church, we are given a further pedigree of William Sr. The earliest Baine in the region was Adam Baines of Hegholme who acquired land in Whinfell in 1428. Adam had a son named William who was living in Hegholme Hall in 1497. William’s son Adam inherited a portion of Hegholme known as Gilfoot but sold it before Easter 1546 to John Rigmaden and Anthony Rose. Adam’s son was probably John, whose son Thomas Baynes of Hegholme was baptized on 14 December 1544. Adam likely had a second son, Adam [Jr.] who had children Mable, Thomas, and James. Adam’s probable third son, William, became the heir of Hegholme after his brothers died. This was the William who was recorded as having a bastard child.

Thus, the correct pedigree for the family is as follows:

Although a William Baines was the father of Mathew Baines who died at sea in 1686/7, it was not likely the William Baines who had sons James and Joseph who lived on what had been Hegholme Hall.

The Mathew of interest’s mother was still living when the William of Hegholme married Sarah and had two or three children. Bigamy is not accepted by the Quakers. No divorce record has been found.

If Mathew was the eldest son of William he would have been the son to have purchased Hegholme. An explanation for him not doing so could have been that his wife and three of his five children had died and he wanted a fresh start in the colonies. It is interesting that William sold Hegholme to James in 1685 and Mathew left the following year. It was more likely a coincidence as was the case of a woman named Deborah who happened to live in Bucks County, Pennsylvania and was placed as a daughter of Mathew when she was from a different family line.

Mathew was probably related to the William of Hegholme but not in a father-son relationship. William’s brother, Joseph, purportedly purchased land in Bucks County, Pennsylvania where Mathew intended to settle, although I have not found a deed to verify that claim.

The problem here is the records are sketchy, there are too many men with the same name in close locations, who all joined the Quaker faith. Until additional records are located my online tree will not have William of Hegholme as the father of Mathew of Wyersdale.