My local historical society is preparing for a fall cemetery tour and decided to focus on pioneering women. My city isn’t very old; it was incorporated in 1887. There are old-timers alive today who still remember some of the founders.

Women are often difficult to research as the norm was to be called by their married name. Today I’m focusing on hunting down the identity and story of Mrs. Edward Henry Becket[t], who founded our first hospital.

Sometimes clues are left behind but we don’t recognize them. In my town is an area known as Whitcomb Bayou. I never thought much of who the bayou was named after. A few weeks ago, a visitor to our museum mentioned that it was named after a woman. That intrigued me and I decided to dig further to uncover the story.

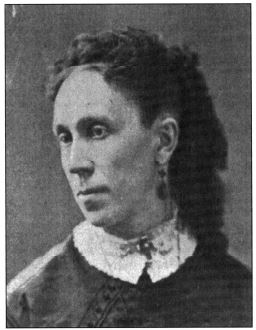

Fidelia Jane Merrick Whitcomb (1833-1888) would be considered unconventional even today. Raised in Nunda, Livingston, New York by parents Hiram and Esther Richardson Merrick who believed in educating their daughters as well as their sons, she ultimately became a teacher of elocution. She married Walter Bruce Whitcomb (1828-1898) and the couple had two children – Clara (1852) and Silas (1859). A member of the Universalist Church, Fidelia became involved at the national level where she met other women who were leaders in their own community, like Dr. Mary Safford, a Boston University professor.

Fidelia and her husband, who was a merchant in Nunda, decided to send their children to Boston for a better education. Fidelia accompanied them while Walter remained in New York. It’s likely that Fidelia called upon Mary Safford when she relocated as soon after, Fidelia applied and was accepted to the first Boston University class for female homeopathic physicians. Mary became Fidelia’s mentor.

Fidelia’s daughter Clara married a lawyer, Ernest C. Olney, in Massachusetts. The couple had no children and divorced. Olney remarried and started a family with his second wife, Hattie. Clara remained childless.

Fidelia’s son, Silas who went by the name Merrick, was accepted to Harvard and completed his degree. He married Zettie Stone Fernald and the couple had one child, Eva Fidelia Whitcomb.

Meanwhile, Fidelia returned to live with her husband in Nunda and opened a medical practice in her home.

She retained contact with her friend and mentor, Mary, who had relocated to Tarpon Springs, Florida to serve as a physician. Mary’s brother, Anson P. K. Safford, former territorial governor of Arizona, had been hired by the Butler Company to develop the company’s Florida holdings.

Fidelia soon joined Mary in what I term a travel medicine partnership. The two physicians advertised in medical journals recommending doctors send their ill patients to recuperate in balmy Florida. Fidelia would spend the winter season helping Mary and return to Nunda in the spring to serve her community during the summer months.

Fidelia died on April 1, 1888, in Tarpon Springs. Per her wishes, she was buried in the town’s cemetery, Cycadia. Her husband survived her and is buried in Nunda. Sadly, there is no gravestone for Fidelia. Her obituary in the Nunda newspaper reported that if she had been buried there, she would have had a large memorial.

My local historical society wants to have a stone erected on Fidelia’s grave but by city requirements, the permission of a descendant must be given. I traced grandchild Eva and discovered she had two children, Louise and Elizabeth, with her first husband, Reginald Worthington. Eva, like her Aunt Clara, divorced. She remarried William Cordon Walton but they had no children.

Eva’s daughter, Louise, married a Harry K. Tucker in Pennsylvania where the family had relocated but the marriage did not last. By 1940, Louise was living with her mother and step-father. The US census reports she was married but she was using her maiden name. She died in 1954; her death certificate stated she was married but her husband’s name did not appear on the form. The couple likely had no children.

Louise’s sister, Elizabeth, married a Mr. Hay[e]s about 1974 when she was 56. It is likely they had no children.

It appears that Fidelia Merrick Whitcomb has no living direct descendants. I haven’t traced her sibling’s children; it looks like there is some family alive today through those lines.

As for the headstone, it’s up to the city to decide.

Regardless of the decision, Fidelia has not been forgotten. We’ll be honoring her in October and every time I pass the bayou named for her I’ll think about her.

This spring, do some digging into your town’s past. An amazing story just might be waiting to be uncovered.