As I’ve blogged recently about Mathew Baines and the Christopher Wood Panel in a church, I’d like to share a very informative court case that pitted James Baines, a Quaker landowner against the local Church of England minister. Both appeared to be stubborn men who would not give up their belief about their rights. Here is a summary of the extended court case:

The following account was taken from the Reverend Canon Ware, M.A. who addressed the Society at Seascale on 25 September 1884 regarding a lawsuit over the curate’s salary in Killington, Kikrby Lonsdale, in the 1600s.[1] Rev. Ware had received a collection of old papers from the Rev. R. Fisher. Rev. Ware had first learned of the papers from Rev. Fisher’s predecessor, Rev. H. V. Thompson.

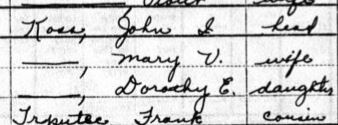

The lawsuit was brought by the curate[2] of the Chapel, William Sclater [Slayter/Slater], who claimed he was due 5 shillings and 10 pence annually from Joseph Baynes Sr and 2 shillings and 8 pence annually from James Baynes, both of Stangerthwaite, Lancashire for messuages and tenements or land.[3] Others named in the suit were Thomas Alexander, Thomas Story, and Samuel Parrett. All were Quakers.

The case was first heard at Moot Hall, Kendal on 11 January 1696.[4] Lawyers for the defendants were Allan Chambre, William Corke, and Robert Kilner, along with gentlemen Anthony and Charles Saule.[5] The gentlemen were included based on a Commission under the Great Seal of England executed under Statute 43 Elizabeth (1601) entitled “An Act to Redress the Misemployment of Lands, Goods, and Stocks of Money Heretofore Given to Charitable Uses.”[6]

Fourteen men were summoned to serve as jurors. They were sworn in concerning the statute and commission. All agreed that “An Ancient Chappell” (sic) in good repair in Hamlett Township aka Chappellry of Killington in the parish of Kirkby Lonsdale had and was being used for divine service and sermons by the curate who brought the suit. All jurors also agreed that from their earliest memories, an annual sum of money or rent was customarily paid by landowners or tenants to whoever held the curate position. Commonly the sum was divided equally in half with the first payment due at Lamas (sic) and the second payment on the feast of the purification of the blessed Virgin Mary.[7] The curate received the funds as part of his salary the Sunday following both holidays.

It was agreed that Thomas Story had not made his payments for the 12 years that he owned or occupied his land at Bendrigg, Killington.[8] There is no explanation as to why curate Sclater waited 12 years to take the man to court so he might obtain his salary.

Witnesses were called and seem to be the oldest inhabitants of the area. Thomas Hebblethwaite of Killington, age about 56, after being sworn in, recalled that the Chapel had been in existence for at least 50 years as he attended school and divine services there, but he did not know when the chapel had been built. Hebblethwaite noted that several men over 80 years of age believed it became a parochial location “very near” 120 years earlier.[9]

Hebblethwaite had heard from several older men, including his father Robert who had died 9 years earlier (1687) and had been over 82 years old at the time of his death (birth about 1605) that a salary, called a stipend, for the preacher was paid annually by the owners or occupiers within the township. This included demesne [10] of Manor Houses. An exception was the manor known as Killington Hall who was thought had been the original family that had given the land for the chapel to be built with space provided for their family’s burial. Since the family had likely donated the land, they were exempted from paying the annual salary to the curate.

This custom was honored until the Quakers were established in Killington about 1663. Landowners not of the Quaker faith continued to pay the curate but Quakers did not. Also noted was mortgaged land beginning in 1607 included terms mentioning the annual salary.[11]

Hebblethwaite also recalled in 1666, carpenter James Taylor, a moderate Quaker purchased land from Richard Hilton in Killington near the Chapel. Hilton showed Taylor his deed from 1625 which stated the tithe was not of corn but of a half peck of meal on silver.[12] Taylor decided to sell the land in 1687 to Quaker John Holme, inserting the tithe clause in the newly written deed. Holme refused to agree to the clause, and it was stricken. Holme later sold the land to Quaker John Bradley; that deed did not include the clause. Bradley returned to Holme after purchasing the land when Bradley learned about the tithe. Holme told Bradley all Killington inhabitants should withhold paying the tithe and it was alleged that Quakers James Baines and John Windson destroyed the original deed noting the required tithe.

The court’s decision was held on 14 June 1697 with the questioning noted for Jos. Baynes, James Baynes, Alexander and Storey. The defendants were ordered to pay the annual sums in arrears and court costs. The curate was permitted to enter and distrain, meaning he could physically go to the property and seize belongings to obtain his due payment. Not surprisingly, the defendants appealed the verdict.

Slayter vs. Jacobum (Jacob) Baynes, Exceptions to the Decree of the Commissioners of Pious Uses, James Baynes noted the following reasons for the appeal:

- The controversy began with the Bishop of Chester which is out of the current jurisdiction.

- The jury in the first trial had insufficient evidence, notably that the chapel was “ancient,” never consecrated, and curates salary was never due.

- Information was not found as to how the yearly rent amounts were established, and they may have been intended to be a (one time) gift for charitable use.

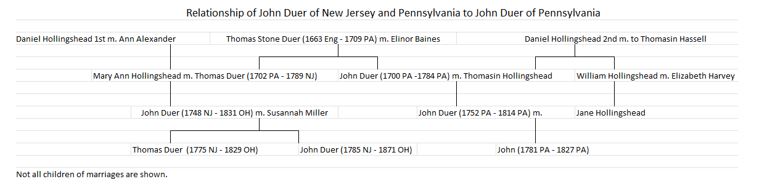

- William Baynes, father of James Baynes, purchased the property 46 years earlier (1651) from William’s father, James Baynes. Grandson James Baynes purchased land from John Robinson of Kirkby Kendall about 1677 and from Robert Hebblethwaite (deceased) about 1662. In May 1685, James Baynes purchased the land his father William had bought from his father, James, in 1651. The current owner, James Baynes, stated his father never paid the tithe nor told his son about it.

- There is no proof that the tithe was anything more than a custom or a free voluntary contribution of benevolence.

- James did not believe the Commissioners had the authority to execute a verdict for noncompliance since it couldn’t be proven that a permanent, inheritable tithe was legitimate and therefore, the curate could not be allowed to seize property for nonpayment.

- James also claimed that the curate did not incur expenses that would be passed on to him.

- There was a question of procedural validity of the court filing by the commissioners.

- The decree was deemed too vague as it did not specify what portion of the property was liable for the yearly payments. Without clear land identification, the decree was flawed and should have been nullified, the heirs released from obligation, and they should be compensated for the court’s errors.

The Rev. Ware found a rough draft of the Answers to Defendants Exception, which was the curate’s counter argument.[13] He claimed the defendants were properly notified but failed to comply and were objecting to stall the case. He requested that the court enforce the decree and further penalize the defendants for their noncompliance. The curate maintained that in the previous trial the defendant’s attorneys contested the evidence regarding the chapel’s consecration and antiquity, the historical obligation to pay the tithe, and the noncompliance by Quakers who claimed they were conscientious objectors. He alleged that James Baynes was one of the prominent Quaker leaders who was behind the idea to resist payment.

The curate provided old rent rolls as further evidence that the ancient, voluntary agreement was valid and applicable to continue. He acknowledged he could not precisely identify the defendant’s lands or boundaries.

It was pointed out that James Baynes was aware of the salary obligation when he purchased land from John Robinson, as Robinson had testified that he had complied with the obligations when he owned the property.

The curate requested that the court required James Baynes to produce his deeds as it was likely that the deeds did contain reference to the salary obligation. The curate claimed James had fraudulently exchanged land with his brother to obscure ownership:

“he (Joseph) has beene sometimes exchanging pticular Lands or Closes with one James Baynes his Brother who had several grounds which lye contiguous thereto, so yt the Lands and Tenemts of the sd Exceptant and the sd James Baynes may be promiscuously till’d and enjoy’d together in Hotch pott nor can be discover’d but by the st Exceptant and his sd Bror or one of them.”[14] This is an interesting statement as it implies that James and Joseph’s father, William, had died intestate and that they were dividing up his land equally which had been given the property to one during his lifetime.

Finally, the curate maintained that James was dragging the case as he had knowledge that the curate had limited financial resources to endure a long legal battle.

On 24 October 1699 Joseph Baynes Sr. petitioned Sr. John Trevor, Master of the Rolls, alleging bias in favor of the curate.[15] A certified copy of Bishop Chadderton’s Grant was given as evidence about the rights and obligations to Killington Chapel. A translation follows:[16]

“To all Christ’s faithful to whom these present letters shall come or whom the matters written below concern or may concern in any way in the future, William, by divine mercy Bishop of Chester, sends greetings in the Author of salvation.

A grave complaint and humble petition has been presented to us by the inhabitants and residents of Killington and Furthbank, in the parish of Kirkby Lonsdale, in our Diocese of Chester. They have demonstrated that, because they are situated and distant from the said parish church by ten, nine, eight, seven, or at least six thousand paces, they are unable to carry the bodies of their dead to the said parish church for burial or to bring their children there for baptism without great danger to both soul and body. Nor can they attend divine services or receive the sacraments and sacramentals there, as Christians are expected and obliged to do by law, due to the distance, the frequent flooding of waters, and the storms that rage in the winter season in those parts, except with great expense, labor, trouble, and inconvenience.

For these reasons, they have humbly petitioned us to grant a license and faculty so that in the chapel situated within the territory or manor of Killington and Furthbank, commonly called Killington Chapel, divine services may be celebrated, sacraments administered, and everything pertaining to divine worship conducted there by a suitable curate or chaplain hired at their own expense and salary. These services should be provided in the same ample manner and form as in the parish church of Kirkby Lonsdale.

Therefore, we, William, by divine mercy Bishop of Chester, being the ordinary of the said parish church of Kirkby Lonsdale as well as of the chapel of Killington, favor the petition of the said inhabitants of Killington and Furthbank, especially as we understand it to tend toward the honor and increase of divine worship. Accordingly, we grant and impart our license and faculty so that in the said chapel called Killington Chapel, situated within the bounds and limits of the manor of Killington and Furthbank, divine services may be celebrated, sacraments and sacramentals administered, marriages solemnized, and the bodies of the dead buried in the same chapel or its cemetery. And the inhabitants of the said hamlet or manor may freely and lawfully hear and partake in these services and activities as freely and amply as they now or recently have done in the parish church of Kirkby Lonsdale.

We grant this license and faculty by the tenor of these presents, to the extent that it is within our authority and lawful power, both for ourselves and our successors. Provided that…

This is a true copy of the license or faculty, at least of what remains of the license or faculty, granted to the inhabitants of Killington and Furthbank, as written in the public register of the Lord Bishop of Chester and recorded therein. A faithful collation with the same copy and faculty written in the said register was made on October 26, Anno Domini 1699.

By me, Henry Prescott, Notary Public, Deputy Registrar.”

The case continued on 23 November 1699 both sides had agreed to examine witnesses, however, one of the curate’s commissioners, Mr. Husband, missed the court date due to a wedding. Although the curate and his witnesses attended, objections by Baynes prevented the commission from going forward.

The next agreed upon court date was 7 December 1699. The curate’s counsel, Josias Lambert, presented the court with costs incurred. The next court date for the witness’s testimony was scheduled for January 1669.

On 18 January 1699, the curate William Sclater was arrested by Charles Saule in Kendal over a debt of 150 pounds. The curate had been attending a commission of ongoing common law cases there.[17] The curate believed this was an attempt to disrupt the Commission’s proceedings, so he instructed his lawyers to have Saule and Nicholas Atkinson, court bailiff, arrested for their actions. The Master of Rolls agreed on 2 March 1699. But Saule had fled and could not be found. Questions then arose regarding his disappearance. Had he been collaborating with the Quakers? Was he overzealous in regard to the case? Or, was their some financial interests involved?

On 11 February 1700 the next hearing occurred. The curate argued that he had the right to arrears and payments but feared stating exactly what his court cost reimbursement request was believing that James Baynes would continue to exploit the system by requesting further hearings. The curate asked that the court minutes record that he can recover costs and that no further delays will occur.

The Lord Keeper agreed to the curate’s request on 20 March 1700.[18]

On 21 March 1701, the Lord Keeper ruled in favor of the curate and offered James Baynes to cover his legal expenses unless he could present a compelling reason to not do so by the next term.

Thus ended the drawn-out legal battle regarding the curate’s salary. Sclater received partial payment for arrears and released Bayne and others from further costs and obligations. Interestingly, William Sclater became the Clarke Preacher of Killington in 1677 and retained the position until his burial on 15 February 1724. He was succeeded by his son, William, who continued until his death on 20 December 1778.

For the descendants of James Baines, the case provided a wonderful genealogy of his sibling, father, and grandfather.

[1] Ware, Rev. Canon, Art. CI. – Killington, Kirkby Lonsdale, its Chapel Salary No. 1. Vol. 8, 1886. Pp. 93-108, digital image; archaeologydataservice.ac.uk: accessed 26 December 2024.

[2] Curate – a minister with pastoral responsibility.

[3] Messuage – dwelling house with outbuildings and land assigned to its use.

Tenement – a piece of land held by an owner.

[4] During this time, the year began on March 25th and not January 1st.

[5] Gentlemen – men of noble birth

[6] A commission under the Great Seal of England refers to an official document that is authorized by the British monarchy and stamped with the Great Seal, signifying the highest level of royal approval and authenticity for important state matters.

[7] Lammas, or Loaf Mass Day, is a Roman Catholic feast day on August 1. The loaf refers to the Eucharist. In the British Isles there were four quarter days with Lammas as the first, followed by All Saints (Nov. 1), Candlemas (Feb. 2) and May Day (May 1). Candlemas was the feast of purification of the blessed Virgin Mary.

[8] Since 1684.

[9] Parochial – relating to a church parish. Likely built about 1576.

[10] Demesne – land attached to the manor that the owners retain for their personal u

[11] 5th Year of the reign of King James I was 1607.

[12] Reign of Charles I began 1625.

A peck is an imperial unit of dry volume equivalent to 2 dry gallons.

Meal – ground up grain as opposed to an ear of corn.

[13] Foul draught – rough draft

[14] Hotch Pott – the bringing together of shares or properties in order to divide them equally, esp. when they are to be divided among the children of a parent dying intestate. The collecting of property so that it may be redistributed in equal shares, esp on the intestacy of a parent who has given property to a child in his or her lifetime.

[15] Master of the Rolls is a high-ranking judge or British official.

[16] Translation from Latin to English by Chatgpt, 28 December 2024.

[17] Petty Bag – an archaic law term meaning records for common lawsuits kept in a bag.

[18] Lord Keeper is an officer of the English Crown was responsible for the physical custody of the Great Seal of England.